Is Triple Win Possible? Guests Return, People Prosper, Nature Thrives

Cardamom Tented Camp. Photo by property.

For decades, tourism has focused on a narrow promise — happy guests and healthy profits — using growth indicators such as visitor arrivals and room occupancy to fuel an industry that contributed a total of USD 10.9 trillion to the global GDP in 2024, according to the World Travel & Tourism Council.

This formula powered decades of growth across Asia. It created jobs, lifted communities out of poverty, and introduced millions of travelers to the region’s cultures and landscapes.

However, this is achieved while externalizing costs that matter most to long-term viability, including biodiversity loss, infrastructure strain, and socio-economic equity.

It is notable that tourism leakage typically accounts for 50–80% of total tourist spending, particularly in the least developed countries, according to The Travel Foundation. In Bali, for example, more than 55% of spending in high-end tourism, notably within four- and five-star hotels, leaks out of the local economy.

The question facing the industry today is no longer whether tourism needs to change, but how deeply.

That was the central focus of Asia Sustainable Travel’s recent webinar, “Is Triple Win Possible? Guests Return, People Prosper, Nature Thrives.”

Bringing together a travel business founder, a conservation practitioner, and a systems designer, the discussion cut through surface-level sustainability claims to examine whether tourism can truly deliver value for guests, people, and nature — at the same time, and over the long term.

The answer from the webinar was neither idealistic nor dismissive. Triple-win outcomes are possible, but only if tourism stops treating sustainability as an add-on, and starts redesigning how value is created, measured, and shared.

This webinar also made clear that incremental fixes are no longer enough. What’s required is a structural reset.

What’s Really at Stake: Tourism Optimizes the Wrong Things

At the heart of the webinar was a shared diagnosis: tourism has been optimizing for the wrong success indicators.

For decades, performance has been measured through metrics such as:

visitor arrivals

occupancy rates

average daily rate

short-term revenue growth

These metrics reward scale, speed, and volume — often at the expense of ecological health and community well-being.

As Jeremy Tran, Co-Founder of Asia Sustainable Travel, framed it in his opening remarks, many industry players first chased a single win (profits and guests), then evolved toward double wins — combining commercial success with either community investment or environmental initiatives.

But double wins, while well-intentioned, still fall short.

Community programs that ignore ecological limits eventually fail. Environmental projects designed externally, without local agency, rarely last. Over time, these efforts become dependent on subsidies, goodwill, or marketing narratives rather than resilient business fundamentals.

A true triple-win tourism, by contrast, suggests that:

communities are co-creators, not beneficiaries

nature is treated as a core asset, not a backdrop

success is measured by what improves locally, not what scales fastest

This shift mirrors the food-system insight from the Breaking the Chain to Save It: How Asia’s Hospitality Can Fix Food Systems webinar: you cannot fix outcomes downstream if the upstream is misaligned.

Michelin Green Chef-owners Summer Le of Nén in Da Nang (left) and Hieu Trung Tran of Lamai Garden in Ha Noi, Viet Nam (right) grow and source food, and reinvest profits locally.

The (Upstream) Demand Problem: When Short-Term Thinking Erodes Long-Term Value

This upstream misalignment between capital expectations and destination health was articulated most clearly by Jacinta Lim, Co-Founder of Seek Sophie, a travel experiences company that was built to counter the dominance of mass-market tourism over discovery.

Seek Sophie began as a response to a simple frustration: authentic, nature-based experiences were being buried beneath algorithm-driven, volume-led tourism products. What Jacinta and her team uncovered instead was a deeper systemic problem.

Demand is therefore designed to maximize short-term yield — even when doing so undermines the assets that generate value in the first place.

When destinations are optimized to extract value quickly, erosion becomes inevitable. Wildlife disappears. Cultural practitioners are priced out. Land, water, and infrastructure are overstretched. These are predictable outcomes of a system where capital is optimized for quick growth rather than sustained development.

From Bali to Komodo, Jacinta pointed to destinations where explosive growth, driven by unchecked demand, has left ecosystems depleted and experiences diminished.

The irony is that this approach isn’t just bad for communities and nature; it’s also bad business.

Tourism is not mining. Places cannot be exhausted and replaced indefinitely. Once the “soul” of a place is lost, it will be nearly impossible to be reinstalled later, Jacinta points out.

Photos by @romanhuber (left) and @akifkeith (right) via Seek Sophie on Instagram

Over-Tourism vs. Under-Tourism: Asia’s Double-Edged Reality

One of the most important — and often misunderstood — insights highlighted during the webinar was that Asia faces two tourism crises simultaneously.

On one end, many destinations suffer from over-tourism: too many visitors concentrated in too few places, overwhelming infrastructure and ecosystems, and frustrating local residents.

On the other hand, a large number of places suffer from under-tourism. They are places of extraordinary ecological and cultural value that receive too little attention to justify protection.

Jacinta shared examples from Borneo, home to some of the world’s oldest rainforests. Where tourism demand is absent, governments are left with few economic incentives beyond logging, mining, or plantation agriculture. In these contexts, responsible tourism can be the non-destructive land-use option available.

This approach requires platforms, operators, and destination marketers to rethink their roles. The challenge isn’t about reducing travel, but about redirecting the visitor flow intelligently.

Responsible demand management in tourism is about:

diverging crowd pressure

matching volume to carrying capacity

aligning incentives with protection

When done well, tourism becomes a defensive force — preserving landscapes that would otherwise be converted to extractive uses. Masungi Georeserve is an embodiment of this approach.

Photo by Masungi Georeserve, Philippines

Conservation-First Hospitality: When Nature Is the Business Model

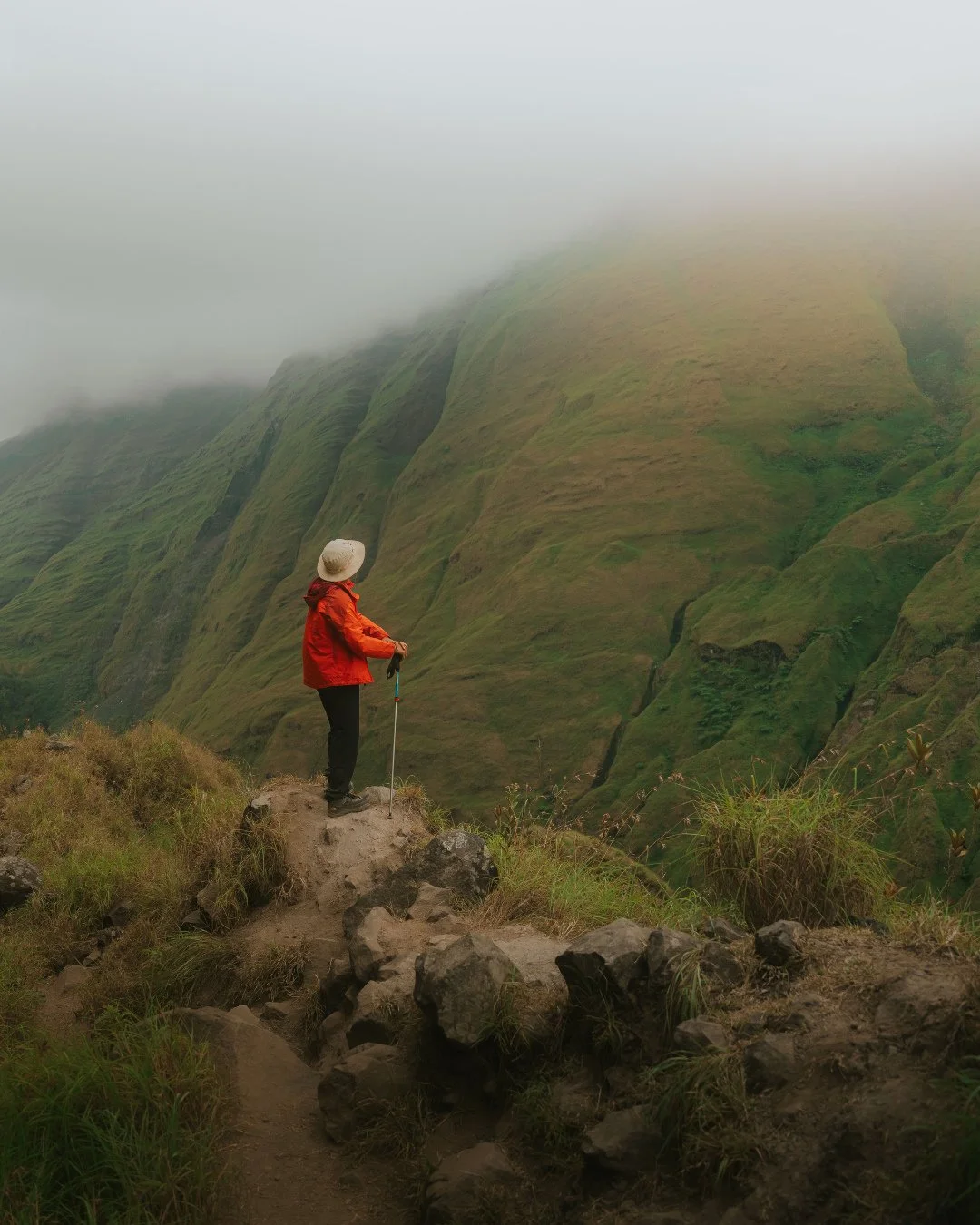

If Seek Sophie illustrates the power of demand redirection, Cardamom Tented Camp demonstrates what happens when conservation is embedded at the core of a hospitality business.

Managed by wildlife-photographer-conservationist Allan Michaud, the camp operates inside Cambodia’s Cardamom Mountains — a region long threatened by illegal logging and land grabs.

The business is stark in its clarity: Without tourism, the forest would be cut.

Cardamom Tented Camp operates under a long-term concession designed explicitly to protect part of the national park. Tourism revenue funds ranger patrols, infrastructure, and local employment. Eight years in, despite COVID, extreme weather events, and logistical challenges, the operation has reached a point where it can fully fund conservation activities.

The camp is not a charity nor a non-profit. It is a business that reinvests revenue into protection rather than extraction. Profit exists, but it is defined differently.

In tourism, funding local ranger salaries and land protection changes the future of the surrounding environment.

The uncomfortable truth, Michaud acknowledged, is that this model depends on tourism continuing. COVID exposed that vulnerability. Yet the alternative — no tourism at all — would have guaranteed ecological collapse.

The takeaway is not that tourism is a perfect conservation tool. It is that in the absence of better economic alternatives, it can be the most viable one available.

Photos by Cardamom Tented Camp

Why Good Intentions Fail: Structural Barriers to Triple-Win Tourism

Andrew Cameron, Founder of Enzyme Consulting, zoomed out to explain why triple-win aspirations so often fail in practice.

The problem, he argued, is systemic.

Tourism, like most sectors of the global economy, was never designed to be regenerative. Its incentives are linear and extractive. GDP, shareholder returns, executive bonuses, and market valuations reward short-term financial performance while ignoring ecological and social costs.

Even sustainability efforts tend to focus on what is easiest to measure, for example, carbon footprints and energy efficiency, rather than what matters most, such as biodiversity, community resilience, or land-use impacts.

The key takeaway is clear: we must measure what truly impacts local communities and ecology, rather than what is easiest or most convenient.

Cameron identified three recurring failure points:

Value leakage — revenue flows out of destinations rather than circulating locally.

Measurement gaps — success is tracked through occupancy and arrivals, not net benefit.

Community exclusion — projects are designed for communities, not with them.

Without addressing these structural barriers, sustainability initiatives remain fragile when they are dependent on individual champions rather than embedded systems.

Photos by Seek Sophie

Rapid-Fire Wisdom from the Frontline

As the webinar concluded, speakers were asked to step away from frameworks and share unfiltered observations from the field.

Several themes cut sharply through the conversation.

Harmful “guest moments” must stop being rewarded. Experiences that allow close interaction with wildlife — touching, bathing, staged encounters — may generate engagement, but they degrade ecosystems, miseducate travelers, and undermine long-term destination value.

Tourism alone cannot solve every conservation challenge. In some contexts, diversified livelihoods — such as sustainable agriculture or community food systems — would create additional stability to revenue generated by tourism. Conservation-first tourism works best when it complements other economic pillars.

Visitor arrivals should be retired as the single most important success metric. High arrival numbers can trigger more harm if not properly managed and if the carrying capacity is exceeded. Net benefit per guest, length of stay, and local economic retention offer more meaningful insight.

Greenwashing reveals itself under questioning. Sustainability claims that cannot be explained clearly and contextually often indicate performance rather than practice.

Conservation is operationally hard. Remote logistics, extreme weather, and fragile infrastructure demand long-term commitment and patience, not quick returns.

The highest-leverage action is open, continuous dialogue with local stakeholders. Relationships — not certifications or technology — determine whether systems hold together over time.

From Growth to Durability: A More Robust Future

The webinar’s most decisive conclusion is also the least reassuring.

Triple-win tourism is not the future of all tourism — and it does not need to be. Some destinations will continue to pursue volume until ecological decline, resident backlash, or diminishing guest satisfaction forces a reckoning. Others will choose a harder path earlier, redesigning for durability rather than growth.

The difference will define viability.

In a climate-constrained, trust-scarce future, destinations that can demonstrate ecological integrity, local legitimacy, and long-term value creation will emerge commercially stronger. Durability will become a competitive advantage, not a virtue signal.

The challenge, then, is not whether triple-win tourism is desirable. It is whether industry leaders are willing to accept its implications: slower growth, redistributed power, and accountability measured over decades rather than quarters.

Triple-win tourism requires discipline. And the destinations and businesses that master it will not just endure. They will lead.