Can Tourism Regenerate Oceans? Why Community Ownership,Not Just Participation, is the Answer

A whale shark emerges from the water near the coast of Donsol, Sorsogon, Philippines. Photo by Eric Kim/WWF-Philippines.

The common perception is that tourism and the environment are at odds: overtourism damages coral reefs, cruise ships pollute, and resorts displace fishing communities. But in October 2025, standing in the coastal municipality of Donsol, Sorsogon in the Philippines, I witnessed a different story: tourism, when driven by genuine community ownership, can become an agent of ocean regeneration rather than degradation.

I was there to speak at the Environmental Planning Conference in Bicol Region, an event that brought together environmental planners, local government officials, tourism officers, academics, and NGOs to discuss pressing issues for coastal communities.

With the theme "Sustainable Blue Economy: Shaping Future Leaders in Balancing Development with Marine Ecosystem Preservation," we found ourselves in a place that proves conservation and commerce can go hand in hand. Donsol, once a quiet fishing town, has transformed into a global ecotourism success story.

The conversation went beyond the basics. We tackled the hard questions: How do we move beyond shallow CSR initiatives? How do we build resilience against super typhoons? And most importantly, how do we get local communities to not just participate in, but own the preservation of their ecosystem?

Here are the key takeaways from the conference, combining my analysis and the insights shared by Ma. Andrea Jane Pimentel-Paz, Project Manager at WWF Philippines. This article highlights the groundbreaking case study of Donsol and practical ways to integrate the Blue Economy into your business strategy.

What is the Blue Economy and Why Should You Care?

For many in the hospitality sector, the "Blue Economy" may seem like just another abstract sustainability term.

It is not.

The World Bank defines the Blue Economy as the "sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and job creation, while preserving the health of marine ecosystems." The oceans feed billions, provide jobs, regulate our climate, and contribute $2.6 trillion to the global economy each year.

For resort owners, tour operators, and tourism planners, the message is urgent: a dead ocean kills your business.

If you operate a beach resort or hotel, your primary asset is not your room inventory; it is the biodiversity outside your window. When the coral bleaches, the tourists leave. When the water is polluted, the bookings drop.

The Blue Economy is not an optional CSR initiative; it is a core business strategy. Embracing it means fully aligning business success with the regeneration and preservation of the marine environment through authentic community ownership.

Can Tourism Really Save the Ocean? Lessons from Donsol on Profit, People, and Preservation

Each whale shark can be identified by its unique pattern of white spots, similar to a human fingerprint. Photo by Eric Kim/WWF-Philippines

The whale shark ecotourism model in Donsol offers one of the most compelling case studies of the Blue economy in action.

Before 1998, the relationship between locals and whale sharks, known locally as butanding, was extractive. They were hunted, valued only for their meat and fins.

In 1998, a coalition of local stakeholders and WWF-Philippines helped establish the area as the first municipal whale shark sanctuary. This move earned Donsol the title "Whale Shark Capital of the World," with Time Magazine even naming the WWF-supported butanding interaction program in Donsol the Best Place for an Animal Encounter.

Such transformation did not happen by chance; rather, it resulted from a radical shift in mindset and policy.

The Pivot: From Hunting to Hosting

The community made a bold decision: a live shark is worth infinitely more than a dead one. They reoriented the entire local economy toward ecotourism. Local fishermen transitioned into roles as Butanding Interaction Officers (BIOs).

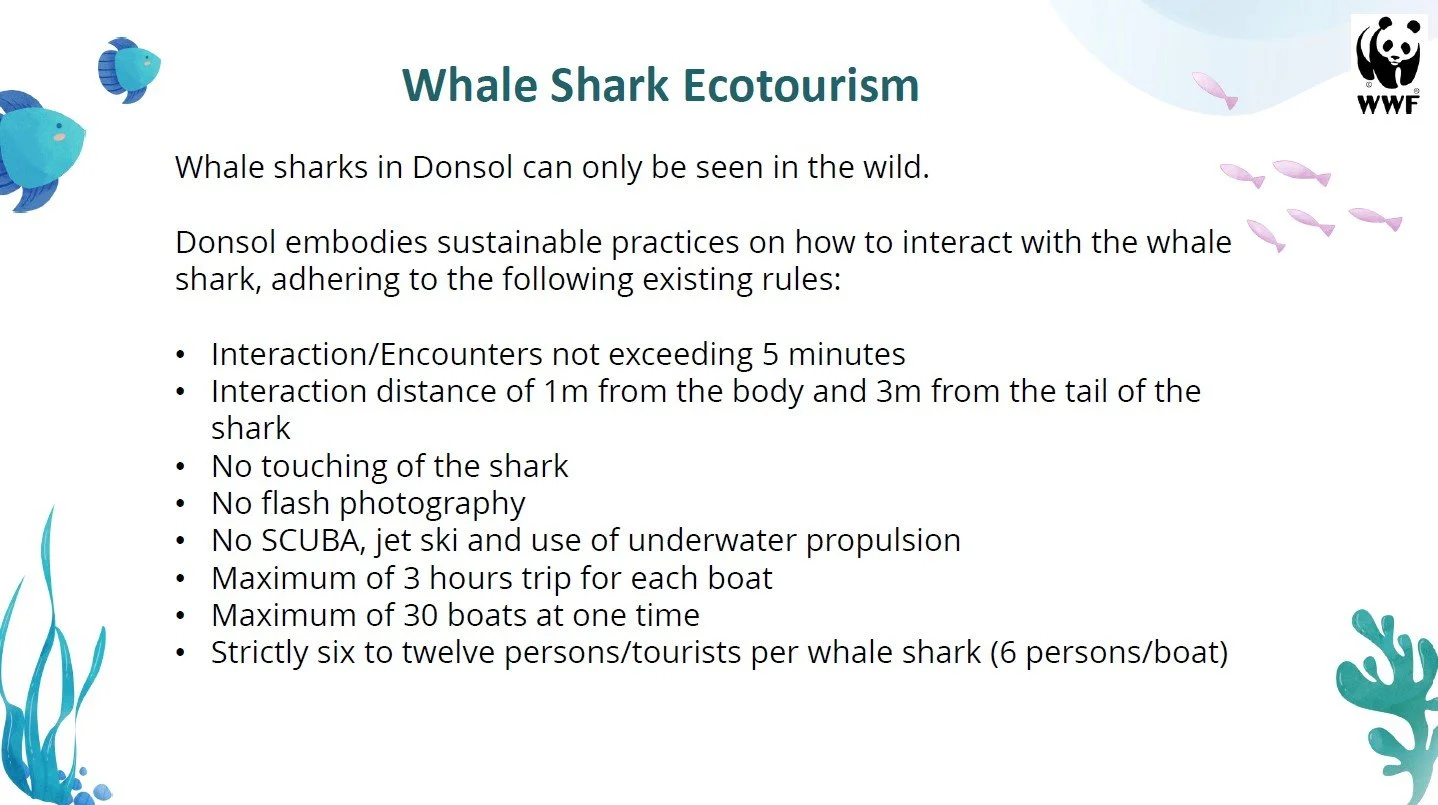

The very people who knew the waters best became the primary guardians of the whale sharks. They serve as spotters, guides, and boat crews. They manage the interactions to ensure the animals are not stressed, strictly enforcing a "no touch" policy and limiting the number of boats.

The secret sauce of Donsol’s success? Community integration and the rigor in their regulations. Locals lead and enforce the rules, prioritizing the ecosystem over guest convenience.

Unlike many wildlife destinations, where rules are loose and boats crowd the animals, Donsol stands out. Here, the local government and WWF established strict guidelines, which they continue to enforce diligently.

This model challenges the old hospitality tenet that "the guest is always right." In regenerative tourism, the ecosystem is right.

Whale shark ecotourism in Donsol is regulated strictly. (Screenshot from the presentation of Ma. Andrea Jane Pimentel-Paz, Project Manager at WWF Philippines)

The Results Speak for Themselves

Data from 1998 to 2025 show a stable population of 782 identified whale sharks in the area. The butanding’s population is stable because the community has a direct financial incentive to keep it that way.

Economic impact: The influx of tourists created a ripple effect. It wasn't just the boatmen who profited. Homestays and restaurants opened, tricycle drivers had passengers, and souvenir shops thrived. The entire municipality saw an increase in income levels.

Ecological impact: Because the community’s livelihood now depends on the presence of the sharks, they have become the fiercest protectors of the marine environment.

Beyond the "Box-Ticking" Exercise

What does this teach us?

In the boardroom, we often talk about "engaging the community." Too often, this translates to hiring a few locals for housekeeping roles or inviting a village dance troupe to perform at a gala dinner—initiatives that are more about image than real partnership.

Authentic sustainability requires moving beyond surface-level gestures and empowering communities as true stakeholders who depend directly on the health of their local ecosystem. When people connect their wellbeing—be it the food on their table or their children’s tuition—to the state of their environment, enforcement becomes an internal motivation rather than an external obligation. You don’t need a coast guard on every corner if the fishermen are fully invested in protecting their own vital resource.

A valuable tool for setting and measuring genuine community engagement is the IAP2 Spectrum of Public Participation. This framework defines five increasing levels of public involvement: Inform, Consult, Involve, Collaborate, and Empower.

The Community Engagement Ladder (screenshot from Rhea Vitto Tabora’s presentation)

The Community Engagement Ladder (screenshot from Rhea Vitto Tabora’s presentation)

Many tourism projects get stuck at the inform or consult stage—sharing information or asking for opinions without genuine power-sharing.

Meaningful, regenerative tourism advances toward collaboration, where communities are treated as partners, and ultimately empowerment, where local people have decision-making authority and receive tangible benefits.

By moving thoughtfully in this direction, hospitality businesses can promote true community ownership, local responsibility, and more resilient tourism outcomes.

Mangroves: The First Line of Defense

Importantly, the work in Donsol extends beyond the whale sharks. To save these gentle giants, the entire ecosystem must be protected. This brings our attention from the deep water to the shoreline, specifically to mangrove forests.

Mangroves are frontline defenders and carbon sequestration powerhouses.

Pimentel-Paz of WWF Philippines shared that carbon stocks in the Ticao-Burias Pass Protected Seascape (TBPPS) range from 168.1 to 710.4 megagrams of carbon per hectare. This is three to four times higher than terrestrial forests. (Donsol is within the TBPPS area.)

For hotels and resorts in typhoon-prone regions such as the Philippines, Vietnam, and Thailand, mangroves are a matter of survival.

The intricate stilt roots of Rhizophora mangroves form a natural fortress against coastal erosion, showcasing nature's engineering at its finest. (Screenshot from Ma. Andrea Jane Pimentel-Paz’s presentation)

The Palompon Proof

During Super Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, the municipality of Palompon, Leyte, was largely spared from the catastrophic storm surges that flattened neighboring towns.

Why? Years prior, the local government had protected Tabuk Island, a dense mangrove sanctuary just off its coast. The mangroves acted as a natural shield, absorbing the energy of the waves before it hit residential areas.

A concrete seawall will eventually crack. A living seawall of mangroves will grow stronger each year, all while sequestering carbon and providing a nursery for the fish that end up on your restaurant’s menu.

Stop Planting the Wrong Trees

However, Pimentel-Paz offers a critical warning: up to 80% of mangrove restoration projects fail.

Why? Many well-meaning companies plant without considering the science. Corporate tree planting programs often fail because they plant the wrong species in the wrong zones.

"We often see monoculture planting of Rhizophora in seafront areas because they are easy to plant," Pimentel-Paz explained. "But in high-energy zones with strong waves, Rhizophora roots break. We need Avicennia or Sonneratia, which have strong root systems that trap sediment and withstand typhoons."

Some of the mangrove species: From Rhizophora's iconic stilt roots to Avicennia's resilient pneumatophores, each plays a vital role in coastal protection and biodiversity. (Screenshot from Ma. Andrea Jane Pimentel-Paz’s presentation)

WWF-Philippines advocates for a science-driven approach, starting with thorough evaluations of soil composition, tidal patterns, and local biodiversity to inform decision-making.

It’s not enough to simply ‘plant trees’. Planting is just the beginning. The real work lies in ongoing monitoring, maintenance, and safeguards. Without a committed strategy for at least 3-5 years of post-planting care, even the best-intentioned initiatives are unlikely to succeed.

Community-led mangrove restoration: Planting and monitoring efforts ensure survival and growth, safeguarding coastal ecosystems for future generations. (Screenshot from Ma. Andrea Jane Pimentel-Paz’s presentation)

WWF-Philippines advocates for a science-driven approach, summarized as the "5Rs": planting the right species in the right place, at the right time, using the right methods, and involving the right people. (Screenshot from Ma. Andrea Jane Pimentel-Paz’s presentation)

Actionable Strategies for Your Business

So, how can you apply the lessons from Donsol to your hotel or travel company?

1. Audit your activities for science, not PR.

Stop generic tree-planting events. If your resort engages in mangrove reforestation, consult with environmental planners or NGOs to ensure you plant the appropriate species for your coastal conditions.

An investment in a proper site assessment will yield far greater returns than a failed photo-op.

2. Engage, don’t just employ.

The "Donsol Model" worked because locals were empowered to take control. In your property, review your supply chain. Are you sourcing seafood from sustainable local fishers? Do you partner with local guides for your eco-tours instead of just hiring them?

When the community feels ownership and responsibility for the tourism product, they tend to protect the resource.

3. Educate your guests on "the no."

Your guests want to be part of the solution. The Donsol experience begins with a mandatory briefing where tourists are told why they cannot touch the sharks.

Hotels must do the same. Use your platform to interpret the local ecosystem for your guests. Explain why you do not serve a certain fish during its spawning season or why single-use plastics are banned on your property.

When guests understand the "why," they become allies.

4. Invest in natural resilience.

Treat mangroves and coral reefs as essential infrastructure. If you are building a coastal development, investing in the restoration of the "Greenbelt"—the natural barrier of mangroves and beach forests—is the most cost-effective insurance policy against rising sea levels and intensifying storms.

Building the Bridge to a Regenerative Future

The solutions to our industry's biggest challenges already exist. They are being tested and proven in places like Donsol. The problem is not a lack of solutions; it is a lack of scale and integration.

As hospitality and travel leaders, you are the bridge connecting capital (investors/tourists) with community and conservation.

If we build that bridge using the old blueprints of extraction and exclusion, the industry will eventually collapse under the weight of a degraded environment and a hostile host community.

But if we build it using the principles of community ownership, scientific rigor, and regenerative economics, we don't just secure our business future. We might just save the ocean.

By embracing the Blue Economy and making the local community a primary stakeholder in your business success, we can build a tourism industry that regenerates value for everyone.

The ocean has cared for us for millennia. It is time we return the favor.

Left photo: Organized by the Philippine Christian University (PCU) in partnership with the Local Government Unit (LGU) of Donsol, the Philippine Institute of Environmental Planners (PIEP) Sorsogon Chapter, and WWF-Philippines, the Environmental Planning Conference in Bicol Region convened experts and leaders in environment and tourism.

Right photo: The author, Rhea Vitto Tabora (Co-Founder of Asia Sustainable Travel) (fourth from left), receiving the Certificate of Commendation from (from left) Architect Rhia Belle Gatdula (President, PIEP – Sorsogon Chapter), Dr. Pritzie S. Rey (Chairperson, MMEP Region V Conference), Hon. Ralph Walter R. Lubiano (Mayor, Municipality of Donsol), and Dr. Jovertlee C. Pudan (Master in Management Program Head and Professor, Graduate School of Business and Management, PCU)